In Part 1, I write about Taiwan’s brush with SARS in 2002-03, the beginnings of the crisis in January, and Taiwan’s initial reactions that put us on a path to getting ahead of the virus.

Part 2:

Before going to bed on February 3, I checked my phone to see an important message sent from school administration to all parents. With a sinking feeling in my heart, I checked, and it was what we had suspected. On February 2, the Taiwanese Ministry of Education had issued a statement saying that the winter break for Taiwanese schools that was due to continue until February 11 would be extended two more weeks until February 25. Many people suspected that international schools like ours would follow suit, and this message confirmed it. We would have three more weeks of extended break, and students would keep up with classes through digital learning. (Also of note, the statement asked employers to provide leave for their employees so that at least one parent could take care of children if need be.)

In my private journal that night, I wrote: What is the new normal? It is face masks all over the place. It is quarantine and cabin fever at home. It is a long winter vacation and staring down at three more weeks of uncertainty. With all the feverish preparations going on around us, I had been looking forward to going back to work, with all its attendant schedules, activities, and some semblance of normalcy. While I was grateful for the chance to spend more time with Steve and Stella, I felt suddenly adrift and cut off from things. As someone who also mainly coordinates and plans events at her job, I was not sure about what the next few months would mean for all of the things we had been scheduling for the spring.

At the same time, Steve and I continued a conversation we had already begun about how to prepare for the worst situation with COVID-19. With a baby on the way and a dog in our family, Steve was on high alert, trying to figure out how to get ahead of this and how to make sure it didn’t impact us. The most dire scenario seemed like we needed to get the heck out of Asia. We could always get on a flight and fly back to the United States, where we would stay with Steve’s parents or my parents, but his more likely because it would mean we could be ensconced in the suburbs away from the busy city centers. How to get out of Taiwan with our dog though seemed like a bigger problem, because animals would probably have stricter quarantine regulations, and pets being abandoned in Wuhan was already presenting as a problem. We talked about that for a while before bringing the conversation down to earth. While the Taiwan CDC and CECC seemed to have things under control and cases were still in the single digits, we wanted to address a much more likely scenario: self-quarantine. The memory of SARS and self-quarantine were still fresh for other teachers at school, and we felt like that was much more of a possibility. While we probably wouldn’t get it if we were careful, we might be cooped up at home without the ability to go outside for a while. We needed to make preparations for that. So we made a long list of things that we thought we would need, like over the counter medications that we didn’t have at home, food and non-perishables that we would find it inconvenient to be without, and some dog medications and supplies that we also wanted. We called it our preparation list, and the next day, we headed to Costco to start beefing up on those items. Even if the worst didn’t happen, we would feel better being more prepared, and we would be able to use up all those supplies eventually. As the Disreputable Dog of Garth Nix’s Lirael would say, “It’s always better to be doing.”

I also wrote in my journal, In my condition, my parents have been calling and asking me to wear face masks. I have acquiesced, and even Steve notes warily that it may have been overly optimistic to go out and eat at hot pot and go to these markets where there’s just a ton of people. Even without the threat of coronavirus, we’re courting flu during this season for sure. This is basically what I mean – even though logically speaking the threat of getting sick is very minimal, and now we’re wearing face masks for anything where we are interacting with other humans (on the MRT, at the store) rather than just ourselves (walking the dog, mostly, or sitting in the park), it still feels psychologically distancing to follow the coronavirus online and at home, watching that red map expand over time, centered on a dark crimson-shaded silhouette of China. Everyone’s being cautious and preventative, but I’m hesitant to call it “overly cautious” now. In all of this, I feel our baby moving inside me. Kicking in the mornings, flutterings during the day, and reassuring me that all is well inside. The kicks are getting stronger, and despite feeling like I’ve got an octopus inside, it makes me smile so much to feel this new life. It is absolutely an amazing thing. I worry about keeping myself healthy, about keeping her healthy, about keeping all of us okay.

So Taipei was holding its breath, but things were due to take a darker turn soon. First, on February 6, Taiwan shut its borders with China, Macao, and Hong Kong. Our friends Henry and Camilla who were living in Hong Kong and had been planning on coming back to Taiwan for the impending birth of their first child had scrambled earlier that week to get an earlier flight back, and when the borders shut, it became clear that their snap decision was one of those decisions that seemed overcautious at first but was excellent in hindsight. It’s worth noting that shutting borders to certain countries, as Europe and the US are beginning to do now, is actually not the stringent ban that it seems to be. For example, you can’t prohibit a citizen of your own country from coming in – that’s what it means to be a citizen. So in this case, Taiwanese citizens like Camilla would have been able to come back. When it comes to Henry, that could have been a bigger question. In fact, a friend who had been traveling in Finland was worried that she wouldn’t be able to return to Taiwan if they transited through Hong Kong. Fortunately, it also became clear that foreigners who already had an Alien Residence Certificate would be allowed back in.

Then on February 7, the other shoe dropped. At dinner, our phones started buzzing simultaneously, evidence that there was a nationwide alert about something. Occasionally, such alerts are sent for typhoons or earthquakes to all cellphones within the area, so we weren’t too surprised, but the contents of this one was a surprise. It turned out that on January 31, the day when I went downtown for yarn and we had hot pot with a bunch of friends, was the day that the fateful Diamond Princess had docked in Keelung, Taipei’s main shipping port and the northernmost city in Taiwan. After the Diamond Princess docked in Yokohama and was found to be carrying COVID-19, Taiwanese officials had been busy tracing the past path of the boat, and found that though the carrier they believed to have infected the boat, a man from Hong Kong, had disembarked already on January 27, the rest of the passengers including some which may have had the virus took a day in Taipei. The text we had received came with a link to Google Maps, where they had recorded the cruise ship passenger itineraries, and depressingly seemed to contain absolutely every single tourist hotspot in the north. With this one move, COVID-19 seemed to be at our front doors. Steve was grimly satisfied that his prediction about the dangers of hot pot seemed to be justified, even if no one had seemed to catch it from this event yet, but this was the spark that fanned the flames of panic in Taipei. January 31 was still the New Year holiday, and most of Taipei’s population had probably been out and about in these locations. A week had already passed, but everyone who had been in those locations anytime between 6:30 am to 5 pm (probably the time that the Diamond Princess was in harbor) was asked to self-monitor their health for the next week until February 14, when the 14-day incubation period for the virus would have passed. My LINE messages from that time record worried back and forth messages with Donna, whose sister had already flown back to the US, and was worried about burning through her sick leave by going home since they had gotten a foot massage that day near one of those locations. I myself had gone to the yarn store just a few blocks away, but thankfully had been wearing at least my cloth mask that whole time.

Three weeks had seemed like a boring eternity to me, and I had idly wondered whether it would be a good idea or not to take a long weekend in Yilan or the south of the island. Now it was coming home to us that the virus was right here in the city, and that it would probably be a good idea to go absolutely nowhere in general. Steve even stopped going as often to his co-working spot just fifteen minutes away because it would mean getting on the public transit more often. Instead, we started taking long walks at night on the riverbanks with Stella. With my expanding belly, I was getting restless at home, but at night in the open air, with a slight breeze, it felt good to stretch my legs and walk for hours. This was the main way we spent time outside in the subsequent few weeks. Occasionally, we made trips to dinner or lunch with a few friends (scrupulously keeping our distance from those who had just gotten back from travel abroad), but more often, we made lunch and dinner at home. Fortunately, the time passed more quickly than I had expected, and with the number of cases continuing to increase linearly (instead of exponentially), the mood was tense but not panicky. When we met with friends or went out, we joked about how great it was to be able to get our house in order, do many loads of laundry, and get as much sleep as we wanted. Even for my friends who had switched to digital learning and online teaching, their first class was usually at 9 am, more than an hour later than usual. So though people complained about spending more of their day in front of a computer, it was not as bad as it could have been. I think the most sympathy had to be given to parents, who were doing their best to entertain and to cope with their young children. While at our school, there were continuing lessons and classes being conducted digitally, many parents I knew were trying to take it one day at a time and not be run ragged by the prospect of being at home for so long with everyone. Fortunately, school still provided a little bit of structure, allowing children to devote themselves to particular subjects throughout the day. I even heard from some friends that this provided a silver lining for their student engagement; some quieter students wrote more on discussion boards than they would raise their hands and say in class. Also, instead of spacing out for a 80-minute class, students were spending 40 minutes doing timed writing exercises, and overall devoting more energy to doing their work than they would perhaps have in class, not that they’d admit to such!

The crazy thing that I took away about COVID-19 was that astonishingly quickly, the new normal took hold, and it became incredibly hard for me to remember what life had been like before this. It was a part of every single conversation I had with friends or parents, Skype calls originally scheduled to update them about the progress of my pregnancy. It just became overwhelmingly the only topic of conversation. When we met up with school friends for drinks one night, the conversation revolved around digital learning, quarantine, and not heck of a lot else. When I looked at Instagram photos from the past few months or watched videos of bloggers walking around Taipei (one of Steve’s favorite things to look at on YouTube), I marveled that not everyone was wearing a face mask, and that people were just mingling around in these crowded spaces without any hint of fear. It seemed like a more innocent time already.

At the same time, we were also learning what consumer panic and supply shortages could look like. On February 8, Taiwan English News reported massive toilet paper sales in Taiwan. Rumors had spread that the increase on demand for raw material used to make face masks would mean that a lower supply of raw material for toilet paper and other paper products. Besides being patently false because toilet paper is made to dissolve in water, and masks need to stand up to some moisture, it was later discovered that the rumor/ social media messages were started by some people who actually worked in the industry and whether erroneously or willfully believed it could be used to their advantage. Taiwan’s been through toilet paper panics before, and fortunately, we were fully stocked even before this thanks to our penchant for being “preppers”, as Steve calls it. However, it made us realize that the true danger did not solely lie in contracting COVID-19. The atmosphere of fear, paranoia, and apprehension made people susceptible to all kinds of groupthink. While we were not in danger of running out of anything in particular, we could easily create our own problems because of ignorance and fear. In response, the Taiwanese government stepped up fines for spreading rumors about COVID-19 to a maximum of NT $3 million (USD $100,000).

Overall, all signs pointed to the Taiwanese government continuing to take this crisis very seriously. The CECC was continuing to work overtime, tracing the contacts of those who had tested positive. Every day, the Taiwan CDC would put out two to three press releases told us how many people were tracked, tested, and put on home quarantine or cleared to go about their daily lives, like this one from February 10. Chen Shih-Chung, the minister of health and welfare who was also the head of the CECC, was basically becoming everyone’s favorite politician. He held daily press conferences and was said to have rushed to attending one after working all night welcoming back a chartered flight of Taiwanese nationals who were returning from Wuhan. His popularity has soared so much during Taiwan’s handling of the entire COVID-19 outbreak that the public is spontaneously paying tribute to him already. Steve was quoting him constantly, and fond of referring to the fact that the current vice-president was an epidemiologist by training.

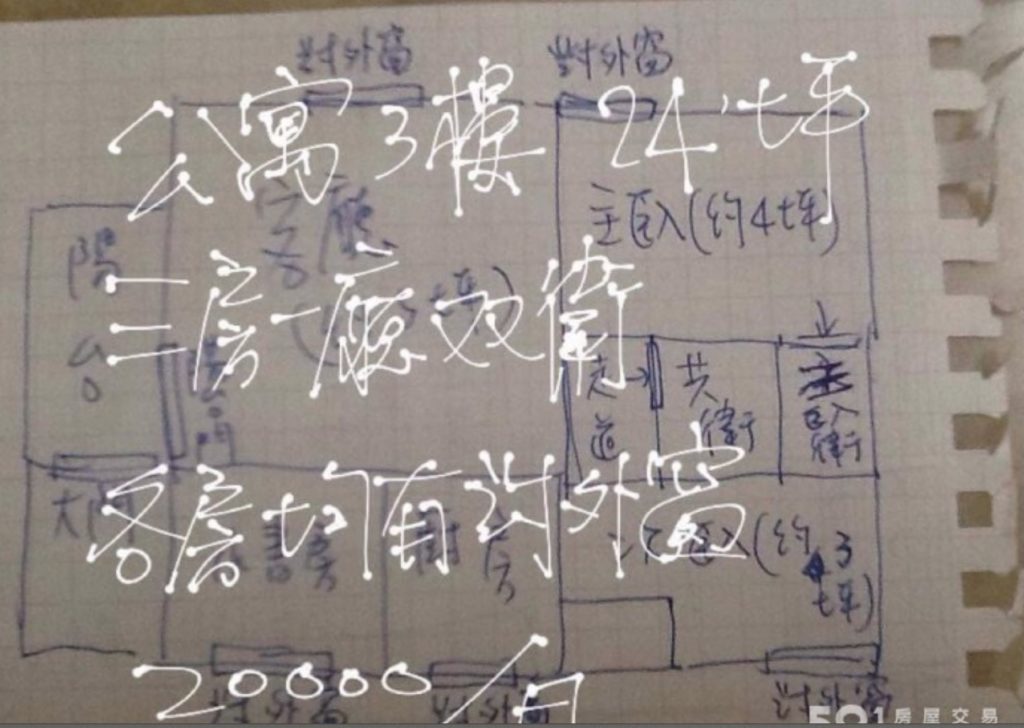

At the same time, digital tools were being made available to the public to help them handle the crisis. Audrey Tang, Taiwan’s digital minister, announced on February 6 at the same time that masks were starting to be rationed a platform to help track face mask supplies. Many apps and maps were being made to track face mask rationing so that the public could identify and visit the pharmacies which still had masks in stock. We used https://coronavirus.app/taiwan to find the ones closest to our house.

Finally, I would be remiss if I didn’t note how worried I was during this phase about anti-Asian sentiment. Several times in February, I shared Facebook articles with friends about the wave of xenophobia that Asians were facing around the world. Children were being bullied in school, people were being beat up in public in Europe, Chinatown restaurants were feeling the lack of business all over the United States, and microaggressions of a million different sorts were being reported all over the world. Imagine how hurtful it was for people to move away from you at the sight of you, for those people to start berating you for wearing a face mask, for people to get up if you sat down next to them. This happened in Europe before there was a single case declared. Here, it is impossible for people in Taiwan to shy away from others on the basis of looking like they were from mainland China. Until you open your mouth (and maybe sometimes afterwards), there’s just no way to know. Everyone’s behind a face mask anyway. But it pained me to see how racism and xenophobia were running rampant elsewhere in the world, given new free rein by the appearance of COVID-19.

Overall, I was feeling pretty ragged. On February 26, I wrote in my private journal, Feeling the baby move is a genuinely great feeling, and would make these days a transport of delight if it were not for the stress of the coronavirus outbreak and the pressure of making decisions, buying things, figuring out where to live. For the past few weeks, my lower left eyelid has been twitching constantly, a reminder that low-level background stress is permeating throughout my life. Maybe an exciting part of becoming a parent… maybe this epidemic which has killed a lot of people already is waiting in the background to pounce. Next week, we will return to school, but I’ve already been called in for a “fever screening training” to make sure we can take the temperatures for everyone coming into school. Steve’s good friends Andrew and Erin, who were planning to come in about a month for spring break, are probably not coming, because everyone in the US is afraid of coronavirus. They’re slightly more concerned about ending up in quarantine afterwards, but it’s really hard to convey how with spring coming, green leaves and sunlight on the trees, with rising temperatures and more folks out of doors not wearing as many face masks, the fear of contagion is more a fear than anything else. It’s really hard to convey that. We don’t know yet what will happen, but the fear of the unknown and the uncertainty when planning further out… it is a very difficult thing to deal with.

In Part 3, I write about going back to school, watching the COVID-19 situation explode in Europe and the US, and why US higher education has made an epic mistake.