A long time ago, when Steve and I first conceived of our world trip (okay about 8-9 months ago for real) we brainstormed all sorts of ways to earn our keep. Most of them revolved around me getting a job in Asia that would utilize my language abilities, but in the end, we decided against most of them for a) not being in my career plan and b) not being conducive to a life of flexible travel, which was what we were most interested in. What we settled on was that Steve would try to do some contract work, like making mobile apps or websites, and I would try to tutor English. I even made some spiffy business cards and picked them up before I left Chicago. While we hoped to earn some cash, we would operate at a net loss overall, and sure, spend a large amount of our savings, but the trade-off, we theorized, was being able to do exactly what we wanted.

Fast forward to the beginning of our third month abroad, and since we arrived in Taiwan, we’ve been buried under personal projects, a crushing inability to get out of bed before 10 am, trying to make our social lives work in a country 14 hours ahead of most of our friends, and a lot of graduate school applications (okay, that’s just me). So far in Kaohsiung, I have succeeded in passing out a sum total of two business cards. So it came as a surprise that our first opportunity for honest income was today!

I’ve seen plenty of requests for a substitute teacher for an English class on Kaohsiung Living, an expat forum website for foreigners in the city. They also seem to be quite in demand, with many people also advertising as substitute teachers. So I didn’t expect much when I replied to one, but got an email back a few days later offering me an opportunity to teach on Monday evening from 4:30-6:30 pm. It would be an afterschool class of 5 young students with the lesson plan already prepped, and I would be paid 550 NT an hour, which is just slightly below the norm of 600 (equivalent to $20 USD). Such supplementary classes in English, math or other subjects, run by private entities, are known as 补习班 (buxiban) and are practically a must for every Taiwanese or Chinese student who is hoping to go to college. I got more details, made sure it wasn’t a problem that I didn’t have an ARC (alien residence certificate) or work visa, and showed up half an hour early.

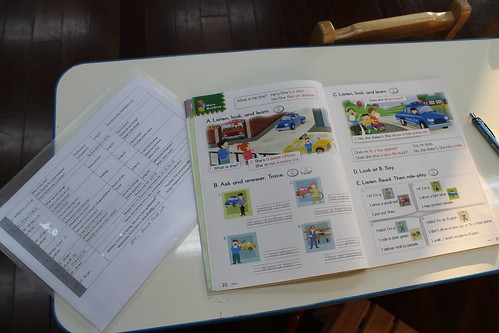

The situation looked rocky at first. It took me two to three tries to get someone to show me the classroom and help me find the lesson plan and textbook. It ended up being a semester syllabus, which is a far cry from a real lesson plan, but I somehow figured out that I was expected to give a small spelling test (on how to spell the numbers 11-20 in English), and then go over a lesson about professions (“the fire fighter drives a firetruck”). Two hours seemed like a long time! I was sweating bullets in the beginning. Steve and I had talked about how many known unknowns made this a much more anxious situation than it should have been. On one hand, I had never been in a Taiwanese school before, so I was sure I’d have “OBLIVIOUS” stamped on my forehead, and I’ve seen how bad the substitute teaching situation could go, given a strange cultural context. Key and Peele, anyone? =)

On the other hand, the guy I was subbing for hadn’t even bothered to ask for proof of English competency aside from seeing what I wrote in my email, and the school administrators weren’t asking for any paperwork or proof that I wasn’t a felon. There was obviously little accountability in this process. The worst thing that could have happened is that I would bomb the entire experience, and I’d never see the kids again.

It didn’t turn out so badly. The five students were adorably dimply and waist-high, ranging from 6 to 9 years old and named generic things like Adam, Tina, and Jessie. At that age, after all, you’re still learning how to push teachers’ boundaries, and if something is interesting enough in class, you might sit still to listen. After the test, we opened the textbook, and learned about taxi drivers, policemen, pilots, and mail carriers. When it came to the mail carrier’s vehicle of choice (“he rides a dark green bike” according to the textbook), I asked them what else you could ride, and received suggestions of “horse” and “elephant.” We then proceeded to guess at the spelling of those words. It was generally a fun time, when I forgot to be stressed.

After an hour and change, the students were getting pretty restless as 6 year olds will, so I called for a five minute bathroom/recess break. That’s when a short interrogation began on where I was from (“the mainland, obviously,” the oldest boy asserted in a worldly manner, “you pronounce English just like you’re from the mainland”). Steve laughed really hard when I told him that. Afterward they came back from the bathroom, I broke the news (through teaching English place names) about being born in Beijing, being raised in Boston (and the United States of America), and moving to Chicago for school. They could grasp the fact that I lived in all those different cities, but what they were flummoxed by was the fact that I claimed to be American. The youngest girl was absolutely adamant that I couldn’t be “北京人” (a Beijinger) and “美国人” (an American) at the same time; another boy backed her up by saying, “那里出生, 就是那里人” (wherever you’re born, that’s where you’re from). I had to explain that I did all my formal schooling in the U.S., hold an American passport, and speak English better than I do Chinese. Moreover, I added, I felt very Chinese sometimes, but I felt that I was more American. I received some dubious glances, but then, these kids (and their parents) had signed up to learn elementary English, not to grapple with complex issues of national and ethnic identity. I moved on before I felt compelled to tell them all about my bachelor’s thesis in sociology, which was on ethnic identity formation and Chinese schools in the U.S. (Email me if you want to read it, because you guys are older than 6 year olds!)

We wrapped things up really quickly, and I gained some popularity for proclaiming that I was not going to assign homework because I wasn’t told I should. Before they left, I had to fill out a short note in their activity books whereupon I signed my name and could choose to check boxes on how they completed their homework (examples: “sloppy and untidy” or “incomplete”) and how they performed during class (“spoke English of own initiative,” “talkative,” “distracted,” or “paid attention”). Then I said that they could go, and all five kids were gone faster than I could have anticipated, with barely a “老师再见!” (“Goodbye, Teacher!”). Thanks, guys. I finished up by correcting the spelling tests they had just taken — one poor girl had messed up pretty much every word; wherever “-teen” appeared in words like thirteen or eighteen, she substituted it with “-tln”. She wrote “ilavn” for eleven, which was pretty charming. The biggest shocker was that the one girl who had the most trouble pronouncing words and was obviously too shy or not engaged enough to read words aloud when prompted was the one who had spelled all the words perfectly. I think I will pin that down to the Chinese penchant for memorization. It won’t take her everywhere, but it’ll serve her well.

I went out to thank the receptionist, received 1100 NT in cash, and promptly spent nearly half of it on dinner for me and Steve. This was an interesting enough experience, and enough like what I had anticipated, in so far as the lesson plan was not really a lesson plan, but the kids were nice and easy enough to deal with for one day. I relied so heavily on being able to explain things in both English and Chinese to make sure the students got the nuances that I’m not sure how most English teachers do it here! Especially when they’re so young and just beginning to learn English. How are you supposed to communicate?? I’ll probably sub again when the chance comes along, because it was interesting and paid a little, but in retrospect, I’m glad I didn’t try to teach English abroad this year. Even Taiwanese schools are obviously not enough invested in it to make sure they have quality teachers and support. I think I’m past the stage where I’m happy to put in 50+ hours a week at a paying job that somehow helps people. Teaching has been a lifelong dream of mine, but it’s not what I’m looking for at this point in my life.

And that was the first money we earned abroad. Fin.

Connie